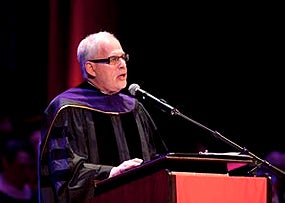

Over the past few months, in preparation for and in reflection of the commencement address I had the privilege of giving at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University on May 12, I watched scores of them on YouTube and read literally hundreds of them as well as their reviews.

Over the past few months, in preparation for and in reflection of the commencement address I had the privilege of giving at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University on May 12, I watched scores of them on YouTube and read literally hundreds of them as well as their reviews.

A few days after my speech, I came upon a piece by actor, director, producer James Franco on the subject of commencement addresses with particular interest.

Having just delivered a commencement address, Mr. Franco shared a few takeaways: “Commencement speeches suck,” they are “easily forgotten,” and at least in his case, crafting one requires the assistance of the likes of Seth Rogen. Mr. Rogen wasn’t available to help me with mine, though thankfully other folks, including my friend Mark Durham, were. There’s no shame in getting help — on this Mr. Franco and I agree.

[Credit Score Tool: Get your free credit score and report card from Credit.com]

While I admire Mr. Franco for his academic prowess as well as his obvious and prodigious talent (hosting the Academy Awards not withstanding), I don’t think he is entirely right about commencement speeches. They don’t all suck; not all of the speakers are famous; and I can personally attest to the fact that they are not all forgotten.

While I admire Mr. Franco for his academic prowess as well as his obvious and prodigious talent (hosting the Academy Awards not withstanding), I don’t think he is entirely right about commencement speeches. They don’t all suck; not all of the speakers are famous; and I can personally attest to the fact that they are not all forgotten.

When I graduated Stanford University in 1971 (am I really that old?), Eric Sevareid, one of the most literate and respected journalists of his time, was the commencement speaker. His speech was eloquent, indeed poetic. I remember it to this day some 40 years later, parts of it verbatim. I remember it because it inspired me, it challenged me, and it made me realize that what we did mattered. It wasn’t just about where I was going — it was about where we were all going.

I know many expect commencement speeches to be little more than a good-natured roast with some platitudes about life being an open book, but I for one think the times demand more. These students are graduating with an unparalleled amount of debt into an anemic economy and job market (For more on that, read my recent columns on the subject). They’ve made incredible sacrifices for their degrees — many, sadly, don’t realize just how much they’ve sacrificed (servicing a six figure loan can have a way of cramping the style of a 22-year-old).

[Related Articles: It’s Time to Solve the Student Loan Crisis and Crowdsourcing the Student Loan Mess]

So, what’s it all for? The system by which we fund higher education in this country may be horribly broken, but that in no way means the people who are a product of it should be written off. They have a vital role to play both in the reform of that system and steering the direction of our country in general. It’s important that these graduates feel empowered to effect these changes. If they don’t — if they’re all too cynical and feel there’s no use in trying — then we’re in big trouble.

In my speech at Rutgers (which I’ve included below) I tried to accomplish what Sevareid did. I focused on the relentless assault on enlightenment and adulthood at a moment in time when our nation seems to need so much of both. I took the speech very seriously.

I’m not particularly famous, but I hope that what I said about those subjects resonated with my listeners the way his speech resonated with me — in times that were turbulent, threatening and dark, just like now.

As Plato noted long ago when enlightenment was itself a new idea: “We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy is when adults are afraid of the light.”

[Free Resource: Check your credit score and report card for free with Credit.com]

COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

MASON GROSS SCHOOL OF THE ARTS

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY

MAY 12, 2012

Speaker: Adam K. Levin

Today we mark a rite of passage.

By your dedication and hard work, you have earned the honor that is about to be bestowed upon you.

You have a ticket to a destination of your own choosing, a chance to forge your own future. And you have chosen a career in the arts. For all this, I salute you.

Artists, scientists, and social innovators have something in common: the love of the question, the willingness to embrace uncertainty.

I would venture to say that everything worth doing demands that. It’s a prerequisite to changing the world.

Not everyone has a taste for this, nor the courage to do it. But then again you’re not like anyone.

As artists, you have chosen a life of questioning, of testing the limits — your own limits, the limits of art, the limits of meaning and reality.

You have chosen truth over comfort, inquiry over complacency — resistance over acceptance.

The world needs you and others like you.

Not to numb audiences with mediocrity or bombard them with trivia. Not to distract and divert them with rough cuts of “reality” reworked to thrill the Entertainment Tonight crowd. But to show them what is, and provoke them to dream what can be.

The world needs honest witnesses — people with the guts to seek the meaning of what they see and feel; to explore, to question — courageously, relentlessly.

The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss said it well: “The scientist is not a person who gives the right answers; he’s one who asks the right questions.” This is true for the artist as well. And it is certainly true for all citizens in a democratic society.

To discover the truths that matter, you as an artist — and as a citizen — must have the courage to question what others take for granted. You must, at the same time, embrace the question as a way of life — which means embracing, in your heart and in the art you practice, the fact of the unknown.

There’s a cost. This path requires courage and agility. It demands a blend of objectivity and empathy. Above all, it calls for confidence and strength of character — the sort of integrity that holds to principle without losing touch with what is real.

But there is a benefit as well. By embracing the question, by engaging the unknown on its own terms, you engage the future.

This may sound like a given. It isn’t.

Because while it may be easy for you, having been schooled in a culture of inquiry, to imagine a future different from what we’re living today, this is not the general case. Fear and doubt have crippled our politics and numbed our culture. The future is seen as a threat, and stasis as the best we can do.

Big dreams are boiled down to big cars, big houses, and big paychecks. In short, hope has been left by the wayside, and imagination is in short supply.

But when I reflect upon the wealth of talent and imagination present here today, I am confident that we can and will do better.

And while there are serious threats ahead — from global warming to urban poverty, from disease and illiteracy to deep-rooted misogyny — I look forward to a transformed future, and new ideas don’t scare me. I am firmly in the camp of composer John Cage who said: “I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones.”

In short, I’m an optimist.

As an optimist, I see the challenges ahead as an opportunity to remake the world we share for the better. I see creative souls like you as the catalyst.

“It’s not what you see that is art,” said Marcel Duchamp. “Art is the gap.”

I would add:

Art is interrogative. It asks. It invites. It opens.

The blank page, the blank canvas, the empty stage, the silent auditorium — each of these is a question waiting to be asked. What will happen there? What will we discover? Where will it lead us?

As you practice your art, it’s your questions that will set those journeys in motion.

Even your closing lines and final brushstrokes, your codas and curtain calls will be a precursor: to thought, to feeling, to action.

That, to me, is the true value of originality — far more important than the profit and fame that flow from copyrights and bylines. Your work is a knock on the door of human possibility, a bell rung in human consciousness, a spur to further invention. The new that you produce is a challenge to be taken up by those who follow — a wager on the future and an invitation to create it.

As the great American playwright Arthur Miller put it: “The job is to ask questions — it always was — and to ask them as inexorably as I can. And to face the absence of precise answers with a certain humility.”

Miller knew the value of questioning. He also knew its risks. His 1953 play The Crucible, which dramatized the 17th-century Salem witch trials, was an allegory of the persecution of artists and activists under McCarthyism.

The following year, Miller was denied a passport to attend the play’s London opening; two years later, he himself was convicted of contempt of Congress when he refused to name names before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Miller’s case exemplifies the gap between questioning and interrogation — between a culture of inquiry and invention and one based on fear and intimidation. And it provides ample evidence — if evidence is needed — that those in power will fight hard to keep the right questions from being asked, to decide which truths can be told and which must be buried, which voices will be heard and which will simply disappear.

Above all, Miller’s case, like thousands more, shows how desperately we need artists who are willing to ask questions to which they don’t yet know the answer — and then follow the thread wherever it leads.

Artists generate turbulence and dissent. They invite new guests to sit at the table, new voices to join the choir. They make people wonder. They give people hope. They open the door to an unknown future.

That power to inspire is precisely why so much effort went into silencing screenwriters, actors and directors in the early years of the Cold War — when Senator Joseph McCarthy flouted every standard of decency to find, brand, and blacklist supposed “communists” in Hollywood.

Actors and directors like Orson Welles and Paul Robeson; authors and playwrights like Langston Hughes, Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Miller himself; conductors and composers like Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copeland — all were pursued by McCarthy. To him and his supporters, they had to be reined in, silenced, and brought down.

To achieve the same effect today, it is common practice to flatten reality into predigested talking points and made-for-TV caricatures, burying truth in a landslide of trivial lies.

This approach offers the tactical advantage of combining the popular desire for a scapegoat with the quick buzz of bringing misfortune to others — effectively boosting ratings, winning elections, or stifling dissent. It’s no wonder that the American political landscape often feels like a bad reality TV series.

Thomas Pynchon summed it up nicely in Gravity’s Rainbow:

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about the answers.”

Mason Gross School of the Arts Commencement Address (cont.) »

You Might Also Like

March 11, 2021

Personal Finance

March 1, 2021

Personal Finance

February 18, 2021

Personal Finance