If you think that credit reporting agencies know and share too much about you now, you’d be shocked to learn what could have been in your credit reports 35 years ago. “Wedding announcements (including the color of the bride’s dress), promotions, arrest records, real estate transactions, anything that appeared in the newspaper” could have wound up in your credit file, according to bankruptcy attorney Eugene Melchionne, who went to work at a local credit reporting agency, the Waterbury Credit Bureau in Waterbury, Conn., in the summer of 1979.

In those days, credit files were manually compiled and maintained. He says one employee’s job was to clip items from the local newspaper so they could be added to the credit file of the person mentioned.

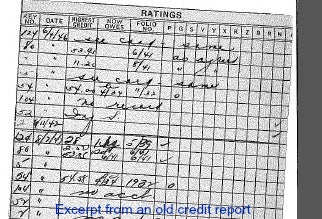

And credit files were actually files; information was kept in paper file folders in large cabinets, arranged alphabetically. If a merchant considering a credit application needed a credit report, an employee at the bureau would retrieve the file, then call the merchant to decipher and relay the coded information.

No Big 3 — Yet

In the 1970s, credit bureaus still often served local communities. “Many were independently locally owned by the merchants who then reported information on their credit customers,” says Melchionne. And the majority of the merchants were locally owned department stores and mom-and-pop type businesses.” He says at one time, tiny Connecticut may have had 20 to 30 local bureaus scattered throughout the state.

In the 1970s, credit bureaus still often served local communities. “Many were independently locally owned by the merchants who then reported information on their credit customers,” says Melchionne. And the majority of the merchants were locally owned department stores and mom-and-pop type businesses.” He says at one time, tiny Connecticut may have had 20 to 30 local bureaus scattered throughout the state.

At the agency where Melchionne worked, everything was done manually. A credit file would be created when someone obtained credit, but it wouldn’t be updated unless a creditor requested current information. So, for example, if a creditor was considering extending you a credit line, they would call the credit bureau which in turn would call your other creditors in order to get recent payment information. He describes it as a very time-consuming process, involving multiple phone calls. Still, “it was a volume thing,” he says. “You could get a bonus if you did more than the goal for the day.”

Written credit reports were reserved for more important transactions, such as mortgages.

“How would the credit bureau know who to call to update the report?” I asked Melchionne, thinking of a situation where someone had obtained additional credit since the last time their file was updated. Applicants would list the companies with which they had accounts on the application as credit references, he recalls.

That meant getting approved for even a small line of credit could take days. The “credit manager” would review the application, contact the credit bureau and make a decision. “Instant credit” would come much later.

Wives Depended on Their Husbands’ Credit

In one of the files Melchionne saved after the Waterbury Credit Bureau closed, a female consumer was referred to strictly by her husband’s name (i.e. “Mrs. John Smith”) when she was profiled in a newspaper column chronicling her contributions to the American Legion auxiliary. When it came to her credit history, it too was combined with that of her husband. In fact, her credit report from the late 1970s had her husband’s name scratched through and her first name was written above it. Perhaps it was changed when he died, as his obituary was also in their file, along with the newspaper clipping detailing her volunteer accomplishments.

Although the federal Equal Credit Opportunity Act, a law aimed at halting discrimination in credit, had been passed in 1975, by 1979 many married women’s credit files were still intertwined with their husbands’. “Wives’ (credit reports) were mixed in with their husbands’,” Melchionne says, “and they didn’t really have their own credit.”

Even worse, “It was chauvinistic,” he says. “They would only offer credit to the husband first and only put the wife on as a co-maker.” Such practices were legally outlawed with ECOA, but it would take time before the then-relatively-new law changed the entrenched system. The system also discriminated against African-Americans at times. Melchionne recalls a lawsuit he was involved with early in his law career where a loan officer kicked an applicant out of his office while using a racial epithet. It resulted in a successful lawsuit under ECOA.

Reviewing Credit Reports

The credit file Melchionne saved now is virtually impossible to read because the codes used back then are not available, but the “highest credit,” column lists amounts such as 11.20 and 54.58, which may have been the highest amount owed to a particular creditor at some point (or perhaps even the credit limits).

Had there been a mistake in their credit reports, it is unlikely the consumers knew about it or would bother to dispute it. Melchionne said that instances of consumers requesting to see their own credit reports were few and far between — maybe “one a week, a few a month.” They were so out of the ordinary that the manager of the credit bureau would handle them personally when consumers came to the office in person to review their reports.

Why didn’t consumers check their credit? Not only were free annual credit reports unheard of at the time, knowledge of credit histories was largely unknown. “I think they probably didn’t even know it existed,” he says of the credit bureau and the files it maintained.

As for credit scores, those were yet to come. FICO recently celebrated the 25th anniversary of the credit score.

When the Waterbury Credit Bureau closed in 1983, it was because it was being purchased by a larger, computerized bureau that had no use for the labor-intensive handwritten files that had been maintained for years. In fact, all files were shredded, with the exception of the few Melchionne saved for historical interest.

It was the beginning of a radical change in the credit reporting world. It would culminate with the consolidation of local agencies into three major, national credit reporting agencies that would collect and distribute billions of pieces of credit information about consumers all around the country. Credit reports would eventually be available to consumers once a year for free, and the codes would be translated into plain English. Credit scores would be introduced, then used widely to help lenders evaluate applications in seconds. Eventually consumers would be able to get their credit scores for free online, which you can do on Credit.com every month.

And the color of your wedding dress would no longer be a part of your credit file.

More on Credit Reports & Credit Scores:

- The Credit.com Credit Reports Learning Center

- How Do I Dispute an Error on My Credit Report?

- What’s a Bad Credit Score?

Image: iStock; inset image courtesy of Gene Melchionne

You Might Also Like

September 13, 2021

Uncategorized

August 4, 2021

Uncategorized

January 28, 2021

Uncategorized